For years now, carbon dioxide emissions in the United States and Europe have been steadily falling — an encouraging sign of progress in the fight against global warming. But on the flip side, emissions in developing countries like China and India have been growing at a very rapid clip.

So one natural question to ask is just how closely these two things are related. That is, are rich countries just “outsourcing” their climate pollution to poorer countries, by shifting their factories overseas?

The answer is basically yes. But as you might guess, there are all sorts of interesting twists and nuances that make this more complicated than it seems.

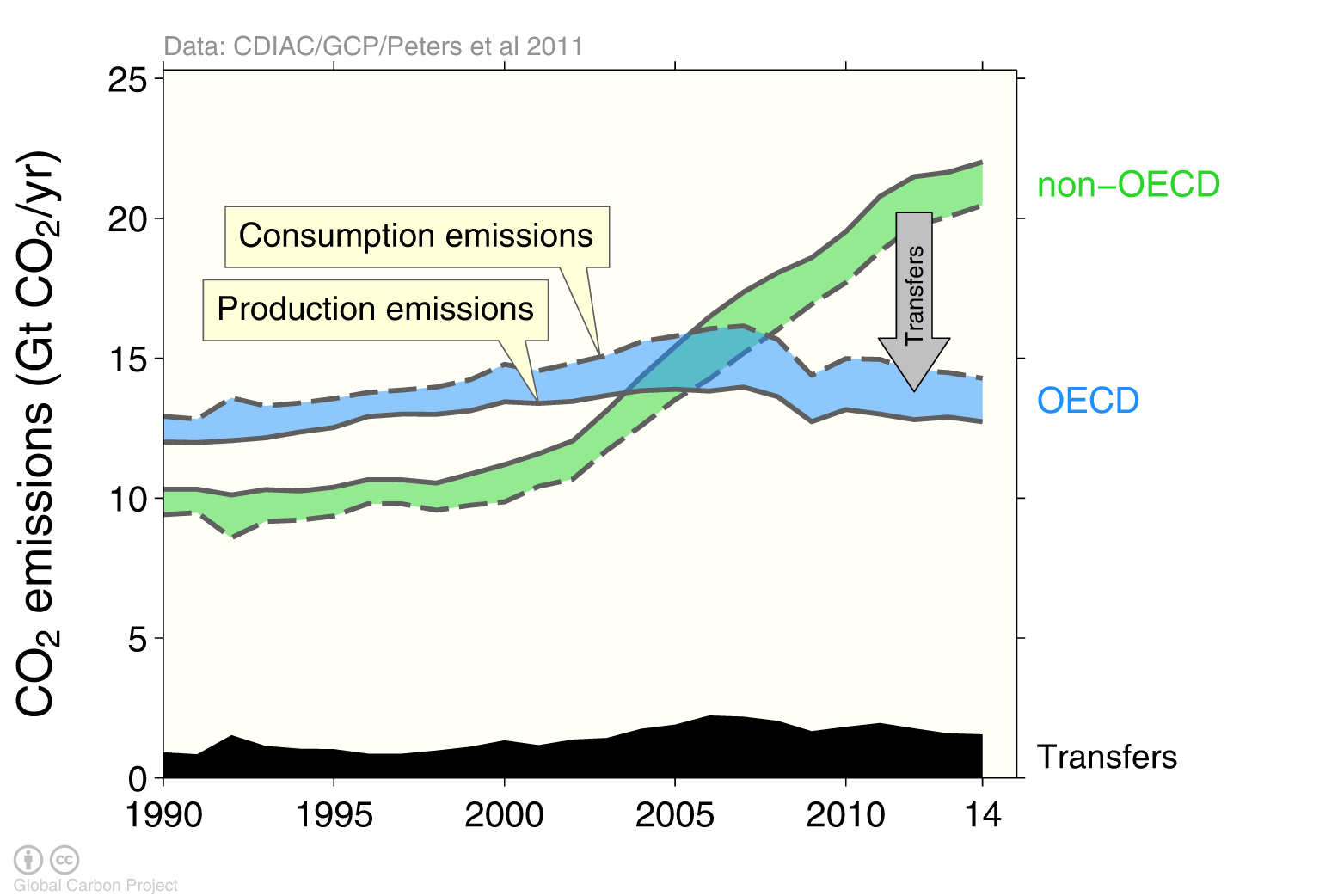

The Global Carbon Project, a major effort to measure CO2 emissions worldwide, tries to measure this outsourcing effect by estimating, for each country, “production emissions” (that is, the CO2 produced within a country’s borders) and “consumption emissions” (the CO2 emitted around the world in the course of manufacturing goods for that country). As you can see on the graph below, wealthy OECD nations “consume” a fair bit more CO2 than they actually emit within their own borders. They have indeed outsourced a big chunk of their climate pollution to the developing world:

During the early 2000s, these “emissions transfers” were growing at a stunning pace, nearly 11 percent per year, as more and more Western manufacturing was shifting to Asia. Factories making computers, electronics, apparel, and furniture would close in the US, open up in China, and then ship their products back home to the US. Americans got the goods; China got the pollution (and the jobs). Since the 2008 financial crisis, however, those transfers have stabilized, even shrunk slightly.

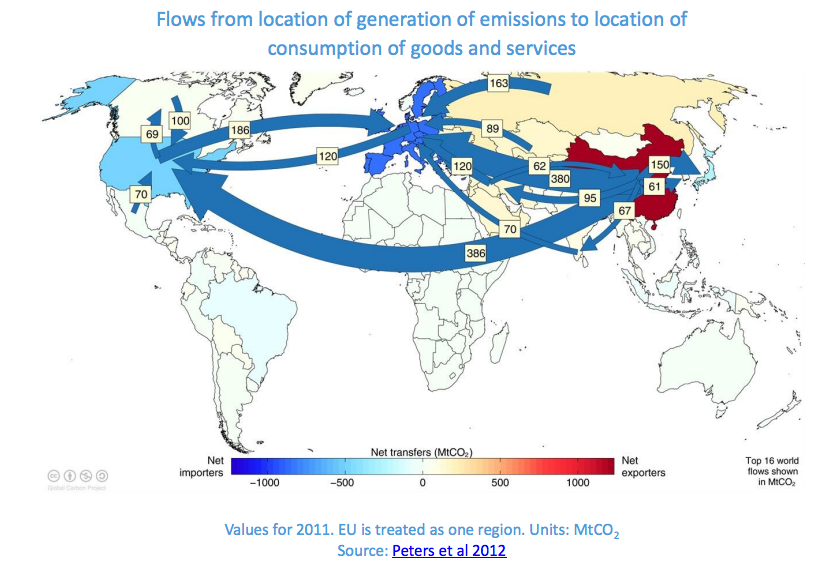

The Global Carbon Project also has a neat map showing outsourcing flows around the world:

That said, these transfers only account for a fraction of the rise in developing country emissions. Which makes sense. In China, roughly 87 percent of the steel and 99 percent of the cement produced is consumed domestically. The vast bulk of the country’s climate pollution isn’t being driven by foreigners; it’s being driven by domestic growth.

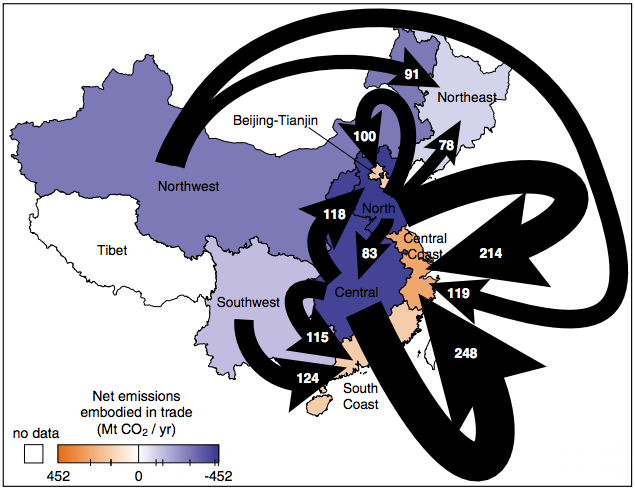

In fact, one notable trend in China is the outsourcing of emissions within the country’s own borders. A 2013 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that China’s richer coastal provinces tended to consume a lot of goods made in the poorer inland provinces. “China is treating its own hinterland just the way the whole world treats China,” Klaus Hubacek, a co-author of the paper, told the BBC.

These are fascinating maps. But as Glen Peters, a scientist at the CICERO Center for International Climate Research and a key figure at the Global Carbon Project, pointed out in a recent post with a few of his colleagues, the actual policy implications of these sorts of environmental flows rarely get discussed.

One big question, they write, is whether this sort of outsourcing should be taken more seriously in international climate negotiations. Under the Paris climate deal, countries are generally held accountable for the emissions produced within their own borders. But is that fair? Should the US or Europe take at least some responsibility for the pollution produced overseas to make the goods they enjoy? So far, this idea hasn’t gained much traction, in part because CO2 outsourcing has been so tricky to measure precisely. But, Peters and his colleagues note, we may want to revise that view as we gain a better understanding of each country’s true “environmental footprint.”

What outsourcing emissions might mean for a (theoretical) carbon tax

Another fun question is what this sort of emissions outsourcing might mean for climate policy going forward. If the US ever got serious about adopting strict limits on CO2 emissions, one thing policymakers might worry about is that many of America’s factories and plants would simply move overseas, blunting the plan’s effectiveness.

In an email, Peters told me there’s little evidence that US or European Union climate policies have caused much “carbon leakage” of this sort to date. In part that’s because US policies have either been too weak or have been focused on sectors like power plants that can’t be shipped overseas. And the EU, for its part, often carves out exemptions in its climate policies for energy-intensive industries like steel or cement. (Most of the current “leakage” happens purely through shifts in international trade flows.)

Still, this is something to consider going forward. In the US, one of the climate policies that wonks love to kick around is a carbon tax, which would increase the cost of emitting CO2 within our borders. Most carbon tax plans envision some sort of border adjustment — in which imports from other countries would be taxed and US exports would be exempt — in order to limit emissions offshoring.

But as this 2015 paper from Donald Marron, Eric Toder, and Lydia Austin of the Tax Policy Center points out, border adjustments for carbon taxes are much, much easier said than done. It’s simple enough to slap a carbon tax on, say, petroleum imports, since measuring the CO2 embedded in a gallon of gasoline is straightforward. But what about the CO2 embedded in cars? Or computers? Or toys? This is quite hard:

There is no way the United States can practically measure the carbon content of goods manufactured overseas because it depends on the production technologies used in making both the goods and on the methods used in manufacturing intermediate inputs (such as steel in automobiles). Complex sets of import duties that the United States cannot show are directly related to any specific characteristic of an imported product might also run afoul of trade agreements.

One possible approach, the paper notes, would be to forget about border adjustments for most products and instead just offer output subsidies for a select few industries that are energy-intensive but also vulnerable to trade competition and hence would be most vulnerable to carbon outsourcing — such as iron and steel, aluminum, chemicals, refining, pulp and paper, and so on. This isn’t perfect, but pretty much any border-adjustment approach runs into legal, economic, or environmental problems, and some amount of clumsy jury rigging is probably unavoidable.

Now, granted, as my colleague David Roberts recently pointed out, it’s vanishingly unlikely that Congress is going to be passing a carbon tax anytime soon, so this is hardly worth agonizing over right now. But it’s a good reminder that trade can make tackling a global problem like climate change that much more complicated.