A crack spreading inexorably across the Larsen C Ice Shelf in northwest Antarctica has surged forward at record rates, bringing the ice shelf closer to cleaving off an iceberg roughly the size of Delaware.

If this occurs, it would be one of the largest icebergs ever observed and could leave the ice shelf behind it in a precarious state, more vulnerable to melting from both relatively mild ocean waters encroaching on the ice from underneath, as well as increasing air temperatures melting ice from above.

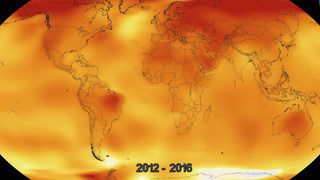

While scientists have said it is not clear that global warming is behind this particular iceberg, the Antarctic Peninsula, where the Larsen C Ice Shelf is located, is one of the most rapidly warming areas in Antarctica, rivaling temperature increases seen in the Arctic.

The scientists from Project MIDAS, which is funded by UK-based research institutions, are using satellite observations to determine the progress that the rift in the floating ice shelf is making. In some places, the fissure is 1,500 feet wide, which is about 600 feet wider than a typical Manhattan avenue block.

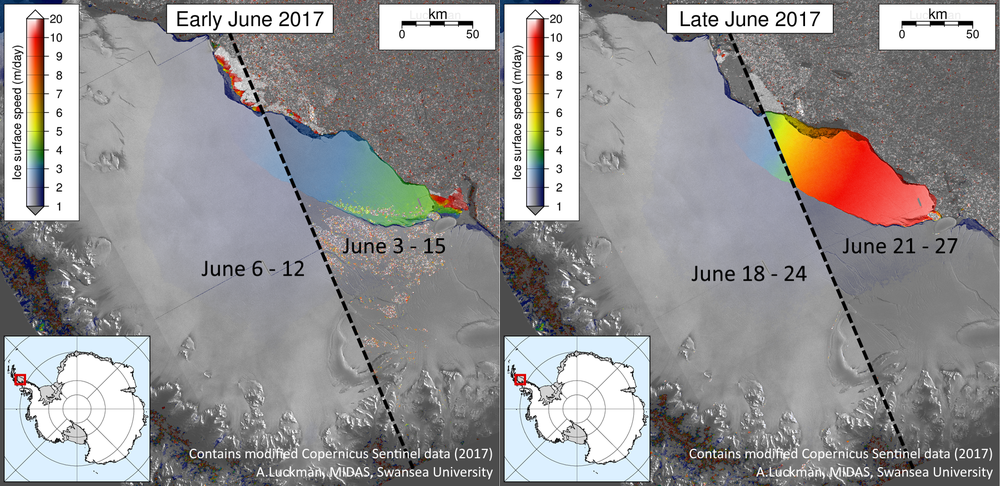

The recent image (right) highlights a significant acceleration over those three days. Comparison of speeds between Sentinel-1 image mosaics in early and late June 2017.

Image: Project midas/esa

In a June 28 blog post, the scientists report: “…The soon-to-be-iceberg part of [the] Larsen C Ice Shelf has tripled in speed to more than ten meters per day between 24th and 27th June 2017.” This means that the crack has moved at least 33 feet per day during the course of this 4-day period.

This is “the highest speed ever recorded on this ice shelf,” according to the researchers. Predicting the exact date that the iceberg will cleave off from the Antarctic continent is tricky, however, since it still remains attached to the ice shelf, but just barely.

“The iceberg remains attached to the ice shelf, but its outer end is moving at the highest speed ever recorded on this ice shelf,” researchers wrote. “We still can’t tell when calving will occur — it could be hours, days or weeks — but this is a notable departure from previous observations.”

The satellite scientists are depending on to detect changes in the progression of the fissure is known as Sentinel-1, a project of the European Space Agency. This satellite is able to detect subtle changes in ground movements and is used for both studying melting glaciers and ice shelves as well as earthquakes and other geological phenomena.

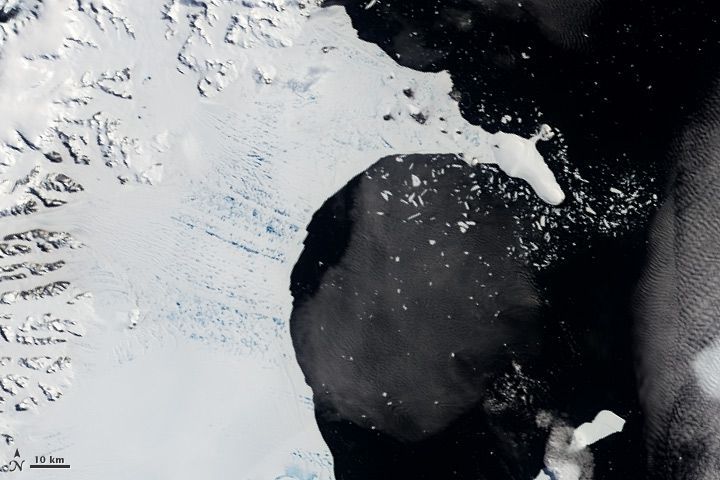

According to Project MIDAS scientists, the most recent data do not cover the tip of the ice rift, but a low resolution image taken just after midnight on June 28 “shows clearly that the iceberg remains attached to the ice shelf at its western end — for now.”

While the calving of large icebergs from Antarctica and Greenland is typical, with or without human-caused global warming, what is happening at the Larsen C Ice Shelf is concerning to scientists studying how Antarctica is responding to a warming planet.

The Project MIDAS team has published research showing that when the fissure in the ice shelf causes the iceberg to calve, the ice shelf will lose more than 10 percent of its area, and leave its front at its most retreated position on record. It’s important to note that the iceberg itself will not raise global sea levels, since it is already floating as part of the ice shelf, sticks out into the Southern Ocean.

“This event will fundamentally change the landscape of the Antarctic Peninsula,” the researchers wrote in their blog post.

The new position of the ice front, which is where the floating ice shelf meets the land-based ice behind it, is likely to be less stable than the previous configuration. This could speed Larsen C’s demise, and make the ice sheet follow the Larsen B Ice Shelf, which disintegrated in 2002.

The collapse of Larsen B actually inspired the opening scene of the film, The Day After Tomorrow.

[embedded content]

A study published in 2015 showed that a reshaped Larsen C Ice Shelf that is missing the Delaware-sized chunk of ice will be much less stable than it has been.

Ice shelves across West Antarctica and Greenland are melting from increasing air and sea temperatures. This is raising alarm bells in the science community, since such floating sections of ice serve as doorstops for the land-based glaciers behind them, and when the ice shelves erode or break apart, they can cause the land ice to flow into the sea.

As land ice melts more rapidly, it is raising sea levels, threatening coastal cities worldwide.

It’s not clear how much of a role global warming is playing in forming and propelling the Larsen C rift, considering that such events can occur naturally. There is some evidence showing that downslope winds may be spreading above average air temperatures across the ice shelf.

However, the Antarctic Peninsula as a whole, where Larsen C is located, is one of the most rapidly warming areas of the continent.