This story is part of a DeSmog series on the influence wielded by the gas lobby in Europe and was developed with the support of Journalismfund.eu

Europe’s gas industry has ramped up its messaging since Russia invaded Ukraine, exploiting fears over energy security to justify projects that risk locking the continent into long-term dependence on fossil fuels, DeSmog can reveal.

Four big industry groups began to post many more tweets portraying investments in gas and related infrastructure as the key to secure energy supplies soon after the invasion started — and maintained this strategy throughout last year, an analysis of their social media accounts found.

The lobby groups were Gas Infrastructure Europe; Gas For Climate; Eurogas; and the European branch of the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers, which represent companies operating pipelines, gas storage, and infrastructure to import liquefied natural gas (LNG). Members include oil majors such as Shell, BP, TotalEnergies, Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Eni, which have posted record profits off the back of the energy crisis triggered by the invasion.

Climate advocates fear the tweets represent the tip of the iceberg of behind-closed-doors efforts to persuade European governments to back long-term investments in gas over the rollout of renewables and energy efficiency needed to achieve the European Union’s climate goals.

“The gas industry wants us to believe that more gas makes us more secure, but more gas leads to more climate change which in reality makes us less secure,” said Ben Franta, senior research fellow at the Oxford Sustainable Law Programme, who analyses legal strategies for holding fossil fuel producers accountable for their climate impacts.

“The gas industry is using today’s news — the war and the energy crisis — to try to lock in more gas for decades, even though the industry knows it’ll be disastrous for the climate and international stability,” he said.

“Big Boon”

The DeSmog analysis of 1,075 tweets by the four lobby groups showed that posts emphasising energy security, or the prospect of an energy shortage or crisis, accounted for about three percent of tweets in the 10 months prior to the invasion. That proportion shot up more than tenfold after the war started, with energy security–related messaging appearing in about a third of tweets from late February to December. Collectively, the four lobby groups have more than 15,000 followers.

The tweets sometimes used hashtags such as #StrategicAutonomy or #SecurityOfSupply.

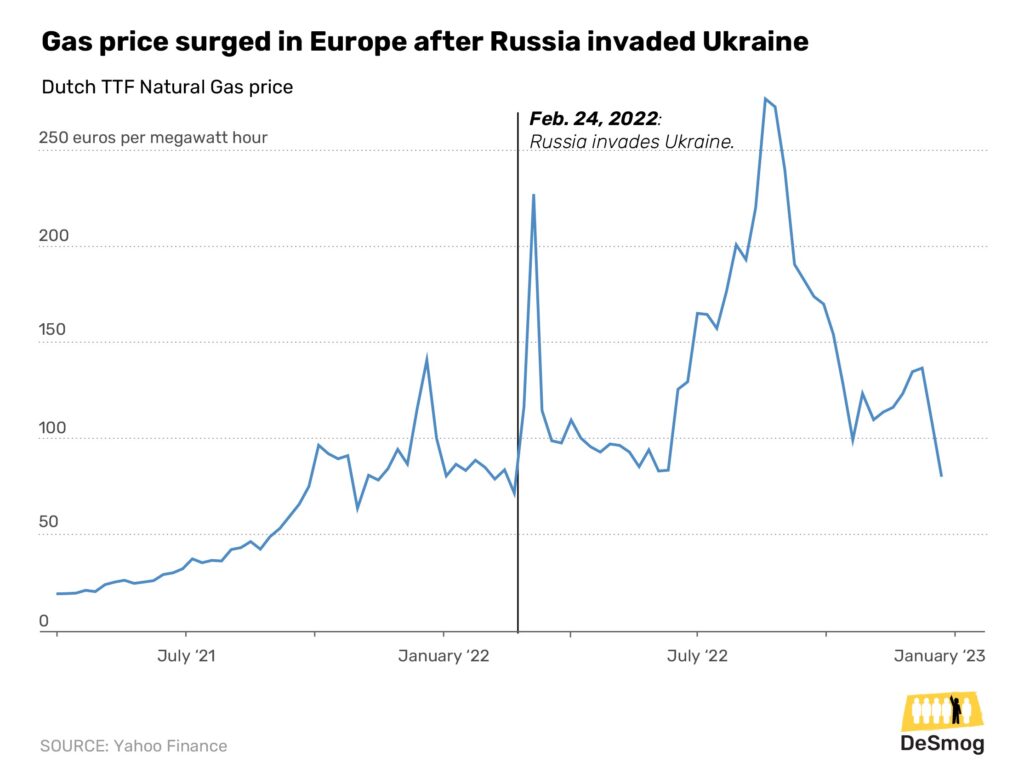

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine last February 24 pushed gas prices to record levels; threatened to cripple European households; raised the prospect of winter shortages; and sent countries reliant on imports of Russian pipeline gas scrambling for alternatives.

Climate advocates acknowledged the need for emergency gas imports to bridge the gap as Europe rapidly weaned itself off its dependence on Russia.

But campaigners say the gas industry is exploiting a temporary crisis to revive long-standing plans to build new terminals to import LNG from suppliers from the U.S. Gulf Coast to Qatar to Australia, and lay new pipelines — hooking Europe on imported gas for decades to come.

That prospect appears to contradict EU climate targets, which imply a reduction in gas demand of at least 35 percent compared with 2019 levels by 2030. The emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane associated with the projects will also undermine global climate goals, analysts warn.

“Before February 2022, it seemed that gas infrastructure projects were starting to flounder, gas was increasingly being seen as a non-viable investment in Europe due to climate targets, stranded asset threats, public protests,” said Greig Aitken of research and advocacy group Global Energy Monitor.

“The war has been a big boon for the European gas industry, and the gas exporting countries that the EU is now more dependent on,” Aitken said.

The surge in new projects risks generating over-capacity that will lead to stranded assets, Aitken warned. Since the invasion, the gas industry has announced that 195 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year in LNG import terminal capacity will come online by 2026, at a minimum cost of seven billion euros, according to Global Energy Monitor data. Before the war, by contrast, the EU imported 155 bcm of gas in 2021 from Russia, including LNG.

James Weston, secretary-general of Eurogas, which represents dozens of European gas companies and several U.S. LNG exporters, said the group’s members had a “serious responsibility” to respond to the energy crisis on behalf of consumers and industry.

“Next winter is going to come around very quickly and there is no room for complacency,” Weston said in an emailed statement. “Our door is open to all climate and energy stakeholders who want to join us in discourse about how we can best manage the dual crises of climate and energy security.”

Gas For Climate referred DeSmog to its website, which says that gas infrastructure would remain important through 2050 as the industry shifted to “renewable” and “low carbon” gases to meet the goals of the 2015 Paris climate agreement.

“Gas for Climate advocates a smart combination of electricity and gas in an integrated energy system to deliver an affordable transition to climate neutrality,” the website says.

Gas Infrastructure Europe and the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers did not respond to requests for comment. Both organisations say on their websites that they are supporting the sector to achieve climate neutrality.

Narrative Shift

The shift towards energy security messaging was most marked in posts by Gas Infrastructure Europe — which represents gas storage, pipeline, and LNG terminal operators — with almost half of the group’s post-invasion tweets discussing energy security.

Within the energy security messaging, DeSmog identified three broad arguments used by the four lobby groups: concerns about winter energy shortages; the need to protect consumers; and support for domestic gas production.

Winter-related messaging was most common in Eurogas and Gas Infrastructure Europe posts; consumer protection was referenced most frequently in Eurogas posts; and support for domestic gas production was found most often in posts by the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers, which also used its Twitter account to applaud national efforts by countries, including the UK, Norway, Denmark, and Greece, to boost domestic gas production.

The surge in energy security messaging occurred against a steady drumbeat of tweets portraying gas as a clean energy source, and promoting gas and hydrogen infrastructure as crucial to the energy transition, throughout the two 10 month-periods analysed on either side of the invasion.

Terms such as “low-carbon gas” or “renewable gas” — which critics say amount to greenwashing since they downplay the industry’s climate impact — appeared in tweets from various lobby groups.

The groups also portrayed a technology known as carbon capture and storage, which traps CO2 emitted from industrial sites, and hydrogen, as solutions for providing “clean gas” and decarbonising the energy system.

Some of the tweets also promoted renewable energy. Campaigners say the gas industry often seeks to foster the perception that gas and renewables are roughly equivalent in terms of sustainability, and can work together in a decarbonized energy system.

“The gas industry will advocate for renewables to advocate for gas alongside it,” said Pascoe Sabido, researcher for the Brussels-based campaign group Corporate Europe Observatory. “They’re saying ‘we want everything’ as a way to open a back door and keep [gas] going.”

Many of the companies in the groups DeSmog analysed are members of the International Gas Union, a global lobby that has also emphasised energy security since the Ukraine invasion, according to an analysis published by InfluenceMap in December.

Shell, BP, and TotalEnergies have also communicated greater “patriotism” in their post-invasion social media posts by focusing on factors including energy security and energy independence, according to a study published in November by research group Solid Sustainability Research.

“To sell imported gas infrastructure in Europe as an energy security idea makes no sense,” said Kingsmill Bond, an energy strategist at RMI, an energy think tank. “There are now superior, cheaper, and domestic low-carbon solutions available, and they will get cheaper over time. Gas will not.”

Italy Pushes the Gas Pedal

EU countries that were heavily dependent on Russia for supplies, such as Germany and Italy, have pushed hard for new gas imports and infrastructure.

The Italian government has signed 11 gas supply deals with exporting countries — more than any other EU country in the past year — according to data compiled by the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Researcher Lorenzo Mario Pastore and colleagues at the University of Sapienza in Rome published a study showing that it would be cheaper for Italy to use energy efficiency and renewables to reduce gas consumption, rather than find new fossil fuel sources.

Drought has underscored Italy’s vulnerability to climate impacts, with Venice canals running dry and lakes and rivers in Northern Italy significantly below their usual level.

Nevertheless, Italy’s government has struck gas agreements with Algeria, Libya, and other African countries since the Ukraine invasion; invested in two LNG import terminals; and, in November, approved government funding for drilling of “Italian gas” in the Adriatic.

“In the face of growing pressure, the Italian government has not taken the opportunity to decarbonize its energy mix with low-cost renewables but has, in fact, been pursuing a policy of substituting gas with other gas,” wrote Luka Vasilj, a policy analyst at Climate Analytics, in an article published by Italian climate think tank Ecco.

Oil and gas company Eni and pipeline operator Snam have both sought to justify new investments in terms of energy security.

“We now have a problem of energy security,” Eni Chief Executive Claudio DeScalzi told a conference call with financial analysts three weeks after the Ukraine invasion. “What we need now, especially nowadays for Europe, is gas.”

DeScalzi and the chief executive of pipeline operator Snam have since advocated for an increase in oil and gas investments in Africa, InfluenceMap has found. Meanwhile, last May, Snam argued that Italy could position itself as a European gas hub to counter “the emergency” threat to gas supplies in the short term — and boost energy security in the long term.

Snam reinforced the message in a series of Facebook and Instagram ads, according to DeSmog’s analysis. After the invasion, the company paid the platforms’ parent company Meta between 1,800-2,100 euros for three ads that discussed energy security, or promoted Snam’s role in guaranteeing stable supplies. These ads made more than two million impressions across Italy.

Eni and Snam did not respond to requests for comment.

The right-wing coalition government of Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, who won snap elections in September, has also justified new gas projects in terms of energy security.

In a move indicative of the country’s changed priorities, Meloni’s government has reorganised what had been the Ministry of Ecological Transition, responsible for environmental protection, into a new entity: the Ministry of the Environment and Energy Security.

“Energy security has always been a mantra to justify gas import infrastructure,” said Alessandro Runci, public finance and multinationals campaigner at Italy-based advocacy group ReCommon. “Since the invasion, it has become a trump card.”

The post Europe’s Gas Lobby Exploits Energy Security Fears in Year Since Ukraine War appeared first on DeSmog.

a skilled workforce,

a skilled workforce,  Tapping into the vast amount of

Tapping into the vast amount of

The

The