For centuries, nomadic families have driven their livestock across Mongolia’s steppe, preserving a way of life that goes back generations. But changes in this vast, desolate landscape have forced them to adapt. Winters have become harsher, and extreme weather events more frequent.

Global warming is affecting Mongolia faster than other parts of the world. “Over the last 70 years, the average air temperature has risen by 2.1 degrees Celsius [3.8 degrees Fahrenheit] – one of the highest increases recorded on Earth,” said Tunga Ulambayar, director of Saruul Khuduu Environmental Research, Training and Consulting.

“By the end of the century, temperatures could rise 5 degrees Celsius,” she said. “Extreme events are growing in some areas. Cases of ‘dzud,’ or extremely severe winters in the Mongolian language, are increasing. Some regions experience heavy summer rain, others go through increasingly intense winter storms.”

Mongolia is one of the last pastoral countries left on Earth. Its economy is dependent on the production of livestock, and around 80 percent of its territory is covered in grasslands. Living at the edge of the inhabitable world, pastoral nomadic people are highly vulnerable to changes.

In response, some herders are forming communities and pooling their resources, in hopes that this will allow their traditional nomadic lifestyles to survive.

Pastures at risk

Around 28 percent of the Mongolian population lives at or below the poverty line, and many people survive on a subsistence basis. Because of this, and the fragile nature of pastures, extreme weather events are often disasterous in Mongolia.

Experts are warning that pastures are at further risk due to overgrazing and climate change.

“A few centimeters more snow than average locks the forage under a thick frozen layer, and causes high mortality among the livestock,” Ulambayar said.

Harsh winters force nomads to the Mongolian capital Ulaanbaatar – unplanned growth is driving rampant air pollution there

“Nomads are forced to migrate to other districts, placing pressure on other fragile pasturelands and communities. Many herders have to move to the city.”

The capital of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, is already reeling under the impacts of rapid urbanization, which include off-the-charts air pollution.

Due to dzud, the winter of 1999 to 2000 resulted in the country losing 30 percent of its herds nationwide. As reported by Ulambayar in the scientific journal “World Development,” 2 million head of livestock, or 20 percent of the national herd, were lost in the dzud of 2009.

And dzud events are projected to increase due to climate change.

The nomads have also observed less obvious changes. “The Khunkeree river used to flow for 25 kilometers [15.5 miles], but these days it only goes 20 kilometers. So it is has shrunk,” said Batkhuyag Tseveravajaa, head of the Uvurkhangai community in the Gobi desert.

Societal changes

Some of the nomads regret the end of the Negdel time, when herds and rangeland were state-owned. Livestock and pastures were equally distributed among herders, pastures were sustainably grazed, and seasonal moves were directed. On top of that, veterinary and social services were provided, and fodder was supplied in the event of a dzud.

But in the 1990s, the fall of the socialist regime resulted in the collapse of this system and the emergence of a market-driven economy.

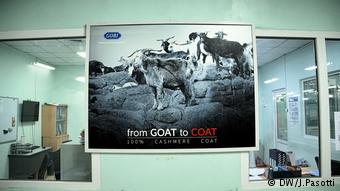

“Herders found themselves alone, suddenly owners of their animals and the land – without support from the institutions. The number of livestock rapidly increased, and pastures degraded,” noted Ulambayar. “After mining, sheep wool and cashmere are the highest traded goods from Mongolia,” she added.

Before the market-driven economy, herders had no reason to scale up their production, as they had a fixed salary and the government provided them with social services.

Today, cashmere is a profitable resource. But it is exploited in an unsustainable way. Since the 1960s, the number of goats kept to produce cashmere has risen from 4.5 million to 23 million.

Stronger communities

Some herders are trying to adapt by forming communities. This allows them to manage their pastures, pool their labor, and slow down – or even halt – the degradation of their land. Herders believe this could be a solution.

After the disastrous winters in early 2000, many herders formed communities for the management of pastures and natural resources, assisted by non-governmental organizations, explained Ulambayar, who studied herders’ capacity to adapt in four districts. She found that those who banded together and pooled their resources significantly reduced household vulnerability to dzud.

The head of the Uvurkhangai community, Batkhuyag Tseveravajaa, is convinced of the benefits. “Together, we collect hay and forage for the winter. We grow vegetables, comb goats, sheer sheep and ensure our river remains clean. These activities are quicker when carried out together,” he said.

Thick ice can often cover the grassland, forcing herders to go further in search of livestock grazing areas

Belonging to a community also comes with social support. Tseveravajaa’s community has a fund of 5 million tugriks (about 2,000 euros) for members who have been severely hit by natural disasters.

“Finding adaptation strategies for Mongolian rural communities is an economic, social, and humanitarian priority,” Ulambayar said.

Until now, communities have shown remarkable resilience, Ulambayar said. The solution to challenges posed by natural and societal changes lies within a dialogue between the herds and the institutions.

“So far, it has proven to work,” Ulambayar concluded.

This story is a part of the Shared Horizons journalism project, which focuses on community-based management of resources as a tool to adapt to changes in the environment. Funding support was provided by the Innovation in Development Reporting Grant Program, operated by the European Journalism Center.