In the coming weeks, President Trump’s advisers are planning to meet to decide whether or not the United States should stay in the Paris climate deal — the key international treaty to tackle global warming. The big showdown was originally set for Tuesday but has since been rescheduled. A final announcement is expected by late May.

The stakes are high: The Paris accord is a non-binding treaty that will depend on persuasion and cooperation to succeed. Nearly every country on Earth has submitted a voluntary (if woefully inadequate) plan to restrain its greenhouse-gas emissions, and the 2015 Paris deal created a formal process by which leaders could help each other ratchet up ambitions over time and push for stronger action at future meetings. If the world’s most powerful country steps back, that entire architecture could erode.

At the moment, many onlookers are betting Trump will stick with Paris, albeit while scaling back US promises to cut emissions under the deal. Some of Trump’s advisers, like Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, have warned of severe diplomatic blowback if America pulls out. And a variety of coal, oil, and gas companies have urged Trump to stay in, noting that there’s no real harm sticking with a non-binding treaty and that it’d be better to try to shape global climate negotiations from within.

But it’s far from certain Trump will stay. During the campaign, Trump repeatedly vowed to pull out, and key advisers like Stephen Bannon are lobbying him to follow through. Scott Pruitt, the head of the Environmental Protection Agency and an ardent opponent of climate action, recently argued on Fox News that the US should exit, calling it a “bad deal” for the country.

A decision either way, experts say, could have major implications for the future of climate talks — and, ultimately, the future of the Earth’s climate itself. So let’s break down the options.

1) What happens if Trump decides to leave Paris?

If the Bannon wing prevails, it would be easy enough for Trump to exit Paris. After all, the accord was never ratified by the Senate and it is basically non-binding.

To leave, the United States could invoke Paris’ formal withdrawal mechanism, which would technically take four years, although US officials could stop participating in any future talks immediately. (More radically, Trump could pull out of the underlying UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, which would take just one year and signal that the US is abandoning all international efforts on climate change.)

By far the biggest question at that point would be how other countries react. Leaders in Europe, China, and India have all insisted they would carry on addressing climate change without the US. But the future arc of climate negotiations — in which countries try to ramp up their climate efforts in the hopes of limiting global warming below 2°C — might look very different.

China, the world’s largest emitter, would be poised to assume a dominant role in future talks, and its leaders have tended to argue for looser oversight and accountability mechanisms within the deal than the US has. “China has historically been a little more wary of strong international procedures and institutions,” David Victor, a political scientist with the University of California San Diego, told me recently. “You might see the treaty become more decentralized and less formalized over time.”

A bigger concern is that, if the US steps back, other countries could decide to scale back their own individual efforts to tackle global warming, says Andrew Light, a former senior climate negotiator at the State Department who is now at the World Resources Institute. “If the US pulls out altogether, the chances increase that developing countries like Brazil or India back away from their own commitments and say, ‘Why should we bother doing this if the world’s biggest historical emitter is completely out of the game now?’” If that were to happen, the chances of avoiding severe global warming would start to look far more dire.

Of course, no one knows for sure what will happen. It’s possible that a US withdrawal could have a galvanizing effect on the rest of the world, and other governments would redouble their efforts to promote clean energy and curb emissions. Most nations still have a vested interest in avoiding drastic temperature increases. But there’s a real risk that momentum for stronger action would be blunted.

There’s also the prospect that the US could face serious diplomatic repercussions for leaving. Europe, China, and other countries could threaten to withhold cooperation on other issues the US cares about. In the most extreme scenario, other countries could threaten to impose carbon tariffs on the US, sparking a trade war. That’s why many Trump allies, like Sen. Bob Corker (R-TN) have argued it may prove smarter to stay in.

2) What happens if Trump decides to stick with Paris?

Now imagine Trump decides to stay in the Paris accord. After the initial fanfare subsides, there’s the crucial question of whether the Trump administration would try to fulfill the Obama administration’s commitments under the deal — like the pledge to cut US greenhouse gas emissions 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025.

Odds are, they wouldn’t. Trump has ordered the repeal of many of Obama’s domestic climate policies, including the Clean Power Plan to curtail emissions from power plants, and various regulations around methane leaks from oil and gas operations. If those policies get dismantled, it will be nearly impossible to meet Obama’s pledge.

One possibility is that the Trump administration simply revises the US emissions goal downward — something they have the legal right to do. (Though it would flout the spirit of the accord, which aims to enhance ambition over time.) A move like that might, in turn, lead other countries to reconsider their own climate plans. If the United States isn’t taking its pledge seriously, why should they?

On top of that, a core part of the Paris deal involves the US pledging $3 billion in aid to poorer countries to help them expand clean energy and adapt to droughts, sea-level rise, and other global warming calamities. The Obama administration already chipped in $1 billion. But Republicans in Congress and the Trump administration have insisted they have no intention of delivering the rest.

Some experts think that Trump abandoning US commitments on aid could be nearly as damaging to international climate efforts as withdrawing from Paris altogether. “For the developing countries, this will be a sign that America is unreliable and that the benefits of staying engaged in climate negotiations are fleeting,” Victor wrote in an essay in November.

That said, Light thinks this outcome could prove less disruptive than total withdrawal. Assume Trump stays in Paris, revises down the US pledge, and dismantles the Clean Power Plan. Even then, Light told me in March, there’d still be enough action from states that you could imagine the US making at least some headway on emissions, even if far less than Obama promised. “And that would still leave the possibility that the US could rebound [on climate action] after one term of Trump,” he says.

3) If Trump sticks with Paris, how might US negotiators shape future agreements?

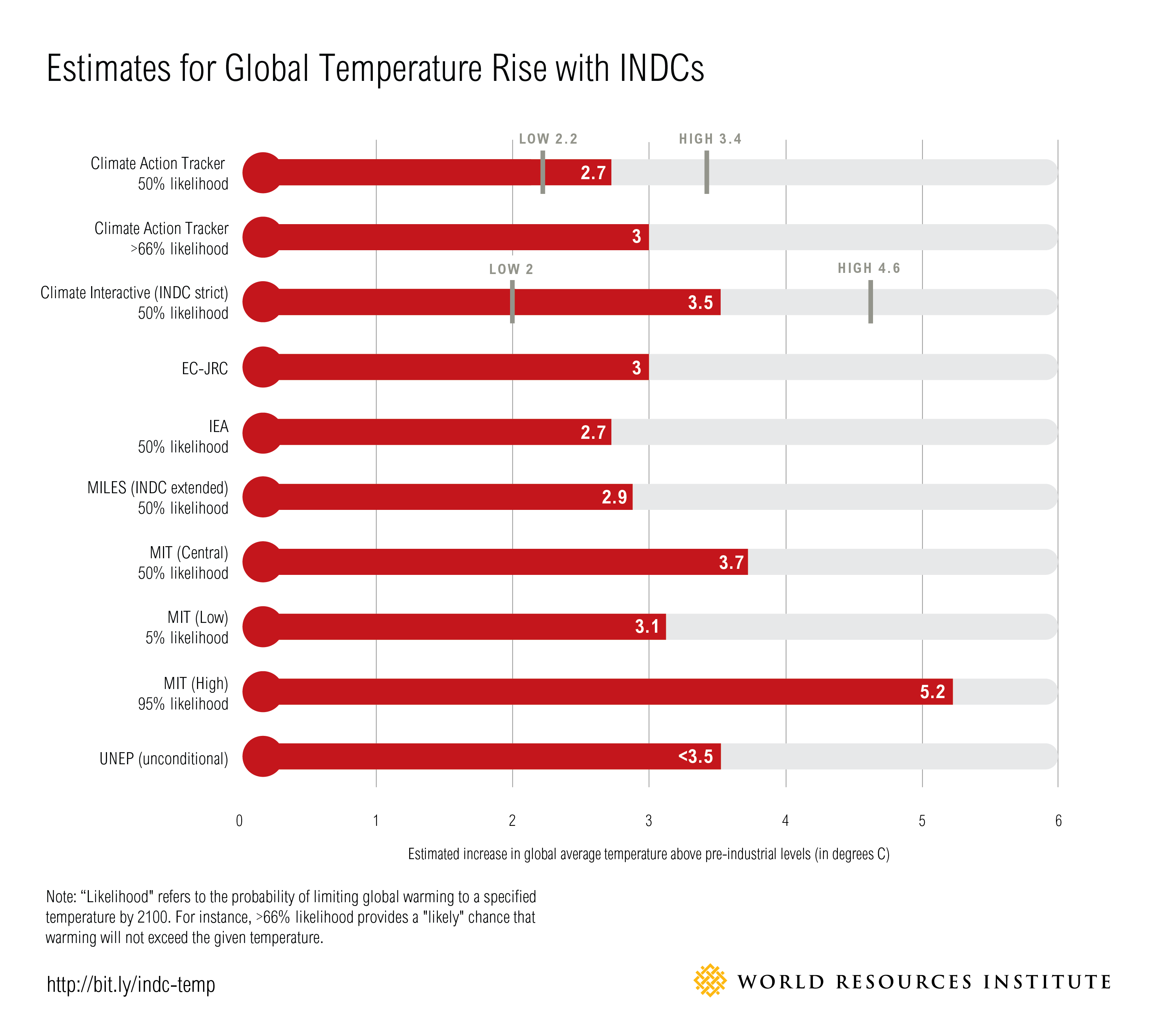

The 2015 Paris deal was only a first step in the long, grinding process of dealing with climate change — and a woefully inadequate step at that. If you add up all the country pledges worldwide, they don’t come close to keeping us below 2°C of global warming. They add up to a severe 3°C or more, depending on which analysis you trust:

The big hope with the Paris accord was that these individual national pledges would be strengthened over time, as countries cooperated and pushed each other to pursue deeper emissions cuts. So a key question here is what role US climate negotiators might play in this ratcheting process.

For example: Over the next two years, negotiators are meeting at the UN to hash out rules around how to review individual country pledges and policies. This “transparency mechanism” could prove contentious. The Bush and Obama administrations had long pushed for strict, uniform transparency standards. China and other developing nations, by contrast, have in the past preferred a “bifurcated” system that holds them to somewhat looser reporting requirements.

If Trump does stay in Paris, one question is whether the US will try to hold developing countries to the strictest transparency standards possible. And it’s worth asking how much leverage the US will really have if it’s also reneging on its emissions targets and aid promises elsewhere.

This sounds like an obscure issue, but for many observers it’s critical. After all, climate change is a collective action problem. Countries are less likely to take the plunge and push for emissions cuts unless they know everyone else will jump with them. “To me, the essence of this agreement is what it can do to strengthen confidence that everyone’s doing their fair share, primarily through greater transparency,” says Elliot Diringer, executive vice president of the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. “With greater confidence, everyone can do more. Weaker transparency rules would make it harder to strengthen confidence and ambition over time.”

Beyond transparency, the world’s nations are also supposed to formally take stock of their progress by 2018 and then submit new — and ideally stronger — NDCs by 2020. But this process of strengthening global pledges could get bogged down if the US is weakening its stated ambitions. It’s not hard to imagine India or China feeling less pressure to step up their efforts if the richest country on Earth is backsliding.

It’s also possible that the Trump administration may push to reorient global climate talks in an entirely new direction — say, by placing a greater focus on working with China to promote carbon capture technology for coal and natural gas. Some coal companies have been urging Trump to stay in the Paris deal to do exactly that.

“My guess is that the Trump administration would come out swinging against the idea of targets and regulations and instead argue that technology is the only way to solve this problem,” says Paul Bledsoe, a senior energy fellow at the Progressive Policy Institute. “They might argue that a crash program on carbon capture is the best way forward here.”

The larger point here is that the Paris climate deal isn’t guaranteed to succeed just because Trump sticks with the agreement. These nuances of what happens to a process that’s already well underway really do matter, and there are lots of ways the US could potentially change the deal — or weaken it — from within.

Further reading:

- Here’s our primer on how the Paris climate deal works. And here’s a scientific “roadmap” showing what countries would actually need to do to meet the Paris goals. It’s daunting.

- The New York Times’ Coral Davenport has more detail on the internal debate within the Trump administration on whether to stay in Paris. Also see Vox’s Andrew Prokop’s piece on the divide between Bannon’s nationalists and the “globalists” within the White House. The latter group tends to comprise the pro-Paris faction.

- Amy Harder of Axios has a nice piece on why many companies — including many coal companies — would prefer that Trump stick with the Paris climate deal.

- Last fall, Neil Bhatiya and Tim Kovach wrote much more on what it would mean for China to take the lead on global climate policy — particularly in places like sub-Saharan Africa.

- How carbon capture could become a rare bright spot on climate policy in the Trump era.